Counter Threat Unit™ (CTU) の研究チームは、特定の業界や地理的場所の組織を攻撃するランサムウェアグループについて質問を受けることがよくあります。こうした質問は通常、ランサムウェアグループが特定の業界を「標的」としていることを強調した第三者機関によるレポートが発表された後に寄せられます。CTU™ の研究チームはこうした懸念を理解しつつも、特定のグループに対する防御に注力することは、ランサムウェアの被害を回避する最善策ではないと主張しています。ランサムウェア攻撃の大半は手あたり次第に実行されるため、組織は攻撃者が何者であっても、あらゆるランサムウェアやデータ窃取攻撃に備える最善の方法を検討すべきです。

攻撃者がどのように標的を選定し、ランサムウェアを展開しているかは、動機によって異なります。サイバー犯罪者の目的は金銭的利益であるため、あらゆる組織が潜在的な被害者です。一方、国家の支援を受けた攻撃者は、破壊活動、スパイ活動の隠蔽、収益創出などの目的を、時には複合的に達成するためにランサムウェアを利用します。したがって、攻撃グループの脅威プロファイルはそれぞれ異なり、標的なる組織も大きく異なります。

サイバー犯罪

金銭的動機に基づく攻撃は、ランサムウェア攻撃の中でも圧倒的な割合を占めています。攻撃者はアクセス可能なあらゆる組織を標的とするため、すべての業界や地域の組織が危険にさらされています。

より多額の身代金を得られると考えてより収益性の高い企業を標的にするグループも存在しますが、ソフォスの顧客テレメトリによれば、ランサムウェアを展開しようとする試みの大半は小規模組織に対して行われています。小規模企業はサイバーセキュリティ予算の制約や、社内にサイバーセキュリティ専門の担当者が不在であることから、攻撃を受けるリスクがより高い傾向にあります。

金銭目的の機会便乗型アクセス

金銭的動機によるランサムウェア攻撃のほとんどが、手当たり次第に実行される機会便乗型で、利用可能なアクセス権の有無に基づいています。このアクセス権は、フィッシングキャンペーンで配布されたマルウェア、情報窃取型マルウェアによって盗まれた認証情報、インターネットに公開されているサービスの脆弱性悪用などを通じて取得されます。手法が何であれ、そのアプローチは無差別かつ非標的型です。そのため、CTU の研究チームは攻撃について語る際、「標的化 (targeting)」という言葉の使用を避け、代わりに被害者が選定されるプロセスを「被害者化 (victimization)」と表現するようにしています。

攻撃者は、攻撃対象を特定するよりも、どの潜在的被害者を攻撃しないかを判断している可能性が高いです。例えば、ロシアや東欧のランサムウェアグループの多くは、ロシアや独立国家共同体 (CIS) 加盟国、そして近年では BRICS 経済圏の加盟国における組織への攻撃を意図的に避けています。これは、ロシアまたはロシアと協力関係にある法執行機関の監視を回避するためです。また、医療や重要インフラ分野の組織への攻撃を避けようとするグループもあります。これは、現地の法執行機関が国際的圧力を受けて対策を講じることを回避するためと考えられます。ただし、そうしたグループの多くは、倫理的・道徳的な理由で攻撃しないのだという根拠のない主張をします。

銀行業界は、ランサムウェア攻撃が機会便乗的であることを示す格好の例です。銀行は収益性の高い組織であり、ランサムウェアによる業務停止は、身代金を支払う強力な動機となります。理論上、銀行はこうした攻撃の主要な標的になるはずです。しかし、CTU の研究チームによれば、ランサムウェアの標的となる銀行はごくわずかです。これは、厳格な規制が適用される業界であり、サイバーセキュリティ基準の順守が義務付けられていることで、他社より脆弱であるために狙われるという「競争上の不利益」が生じないためと考えられます。その結果、投資が行われ、管理フレームワークが明確化され、境界は適切に保護され、ネットワークは侵害の機会を制限するように設計されています。規制の緩い業界の組織は、強固なサイバーセキュリティ対策の導入が銀行業界のように奨励されていないため、機会便乗型攻撃に対してより脆弱です。例えば、製造業においてセキュリティ対策を強化すると、企業のコスト基盤が増大するため、競合他社の製品を相対的に安価に見せてしまうことになります。

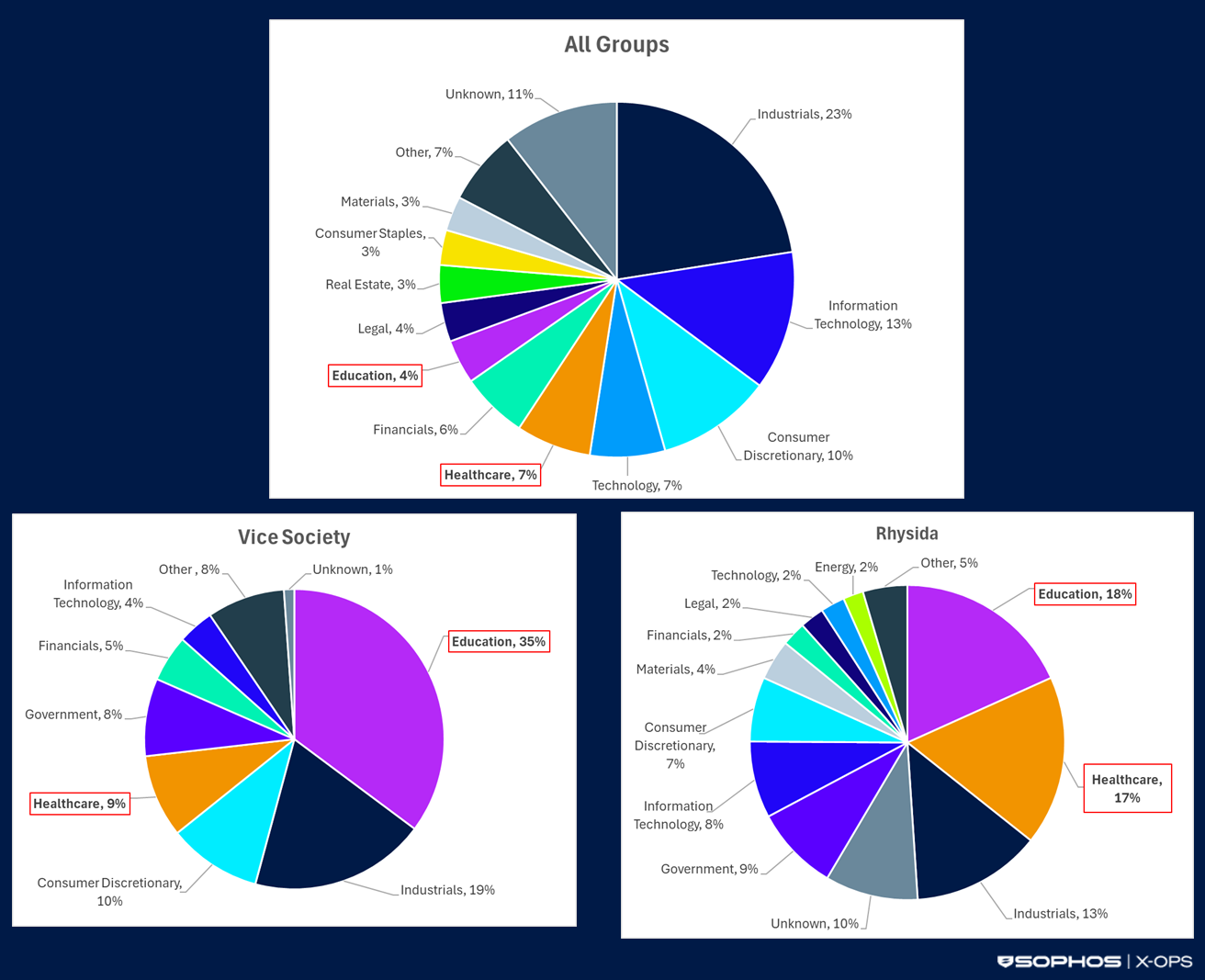

図 1:2021年 5月 1日から 2025年 12月 31日までの期間、全ランサムウェアグループによって被害者化された業界 (Vice Society および Rhysida の内訳との比較)

被害者の選別基準は、グループの成熟度、専門性、リスク許容度によって大きく異なると考えられます。特に、RaaS (サービスとしてのランサムウェア) スキームにおけるアフィリエイトの存在が、このプロセスを極めて予測困難なものにしています。特定スキームのアフィリエイトは共通の手口 (プレイブック) を用いることもありますが、より有利な条件を求めて複数のスキームを渡り歩くため、攻撃者の特定や侵入活動の予測を一層難しくしています。

アフィリエイトを募集する際、特定の業界や地域への攻撃禁止、被害者の収益が一定額以上であること (攻撃に費やす時間に見合う利益を得るため) などの条件を明記するグループも存在します。しかしながら、経験の浅いアフィリエイトの中には選別プロセスを全く行わず、データを窃取しランサムウェアを展開するまで、自分が誰を標的にしたのかを完全には把握していないケースがあります。攻撃者が潜在的な影響を適切に評価しなかった場合、ランサムウェアの展開が意図せず壊滅的な結果を招く可能性があります。例えば、2024年 6月に Synnovis にランサムウェアを展開した Qilin アフィリエイトが、それがロンドンにおける国民保健サービス (NHS) の業務に甚大な損害をもたらすことを予見していた可能性は極めて低いでしょう。

サプライチェーンへの侵入

一部の攻撃者はサプライチェーンの侵害に注力しており、そのため実際には無差別なランサムウェア攻撃やデータ窃取攻撃が、あたかも特定の組織を狙った攻撃のように見えることがあります。例えば、Clop ランサムウェアを運用する脅威グループ GOLD TAHOE は、マネージドファイル転送 (MFT) サービスのゼロデイ脆弱性を突くエクスプロイトを作成し、データ窃取と身代金要求を行っています。このグループは特定の組織を狙って恐喝しているわけではありません。被害者は、たまたま攻撃対象となったサービスを利用していたために巻き込まれたに過ぎません。脆弱性の悪用とデータ窃取は自動化され、大規模に行われるため、被害者の選別が行われるのは、グループがデータを収集し被害組織を特定した後のことです。GOLD TAHOE が収益や業界に基づいて特定の企業を優先的に恐喝している可能性はありますが、身代金要求自体は定型的で、個別の組織を対象にしていないように見受けられます。いずれにせよ、このような高度な技術を駆使した活動は、一般的なサイバー犯罪グループとしては異例です。

名声

サイバー犯罪者によるランサムウェア活動において、被害組織の選定基準が変化するもう一つの動機は、仲間からの称賛です。例えば、CTU の研究チームが GOLD HARVEST として追跡している、若年層の緩やかな集団である Scattered Spider が、どのような基準で標的を選んでいるのかは明らかではありません。しかし、このグループのメンバーにとって、攻撃の主な動機は必ずしも金銭的利益ではありません。GOLD RAINFOREST (別名 Lapsus$) や Lulzsec といった過去のグループと同様に、攻撃は金儲けのためというよりも自慢や称賛を得るために行われている節があり、その結果として有名な組織が頻繁に被害を受けています。GOLD HARVEST は、その活動において極めて高い能力を示してきました。例えば、Oktaのアイデンティティ管理ソリューションである Okta の認証情報を奪取することで、その後、Okta を認証基盤としている企業を次々と標的にすることに成功しました。

このグループが用いる手法の一部には、他のサイバー犯罪グループやランサムウェアグループのような「たまたま入手したアクセス権」に依存しない標的選定が含まれています。主に英語を母国語とするメンバーは、ソーシャルエンジニアリングを通じて選定した組織へのアクセスを試みます。具体的には、ヘルプデスクに電話をかけてパスワードリセットや多要素認証 (MFA) デバイスの登録を行わせます。常に成功するとは限りませんが、従来のサイバー犯罪グループやランサムウェアグループとは異なる脅威を象徴しています。

とはいえ、このグループがアクセス可能な機会を突いて被害者を攻撃している可能性も否定できません。CTU の研究チームはこれらの攻撃について特別な情報を有してはいませんが、2025年の Marks & Spencer (M&S) および Co-op への攻撃において、サードパーティの IT サプライヤーである Tata Consulting Services (TCS) が何らかの役割を果たしたとの噂があります。なお、TCS は自社のシステムやユーザーが侵害された事実を否定しています。

ブランド構築

RaaS オペレーターは、アフィリエイトを惹きつけるために自らのブランドを確立しようとすることがあります。オペレーターはアフィリエイトに対し、身代金が支払われる見込みの有無にかかわらず、あらゆる組織を標的にするよう促す場合があります。これは、被害者数を増やして、そのスキームの影響力をより大きく見せることが目的です。しかし、この手法は RaaS オペレーターにジレンマをもたらします。「アフィリエイトにとって魅力的な影響力を保ちつつ、法執行機関から注目されるほどの被害を出さないようにするには、どうすればよいか」という問題です。大半のグループの目的は単なる金儲けであり、自らの活動にリスクをもたらすような組織を標的にするのは賢明ではありません。そのため、彼らの選別プロセスには、病院や慈善団体といった注目度の高い組織を対象から除外する配慮が、おそらく含まれています。さらに、スキルの低い攻撃者がランサムウェア攻撃に関与することが増えていることは、現在の状況が「数こそ多いが質は低い」、つまり侵害された組織への影響が比較的小さくなっていることを意味します。この影響度の低さが、身代金を支払う組織の割合が低下し続けている理由の一つであるかもしれません。

国家支援型ランサムウェア

国家支援型のランサムウェア活動は、一般的に機会便乗型ではなく、特定の組織を意図的に標的にします。標的の選定は、攻撃者の動機や目的によって大きく左右されます。国家支援型の攻撃は、ランサムウェア攻撃全体の総数から見れば極めて小さな割合ですが、

CTU の研究チームは、国家支援型または政府系ランサムウェア攻撃において、主に次の 3 つの動機を確認しています。

収益の創出

収益創出を主な目的とする国家支援型グループは、他の目的を持つグループに比べ、ランサムウェア展開において標的を限定しない傾向があります。複数の北朝鮮系脅威グループが収益創出目的でランサムウェア攻撃を試みており、その範囲は Maui のような標的を絞ったランサムウェアから、無差別型ランサムウェアワームである WannaCry まで多岐にわたります。被害組織は医療分野に集中しており、これは人命への潜在的リスクや法執行機関による報復を顧みない政府が、「医療機関は身代金を支払う可能性が最も高い」と判断し、意図的に選択している可能性を示唆しています。

同様に、イランの脅威グループ COBALT MIRAGE によるランサムウェア攻撃でも、国家主導の作戦との関連性がありながら、政府の利益とは一見無関係な標的を選定するという特異な組み合わせが見られました。その後の調査により、イランの民間企業がイラン革命防衛隊 (IRGC) の活動に関与する一方で、同様の手口で私利目的のランサムウェア攻撃も行っていたことが判明しています。

他の活動を隠蔽するための煙幕

中国を拠点とする脅威グループ BRONZE STARLIGHT など、特定の国家支援型攻撃者は、スパイ活動の隠れ蓑としてランサムウェアを展開します。システムを暗号化することで侵入の全容を示すフォレンジック痕跡を隠蔽すると同時に、「ランサムウェア攻撃を受けた」という筋書きを見せることで、調査担当者の注意を攻撃者の真の目的や実際の被害から逸らさせます。したがって、このような煙幕活動におけるランサムウェアの展開は、特定の組織を標的に行われ、他の国家主導攻撃と同様に集中的かつ断固とした姿勢で実行されます。

妨害、嫌がらせ、影響力行使

ランサムウェアは強力な妨害ツールであるため、敵対的と見なした国の組織の業務を妨害したい攻撃者にとって有用な手段です。これにより、攻撃者の特定や動機の解明が困難になる場合があります。例えば、CTU の研究チームは当初、中東の組織に対する DarkBit ランサムウェアの展開を「金銭目的のグループ (GOLD AZTEC) によるものと考えていましたが、その後、過去の標的選定や手法に関する証拠が明らかになるにつれ、このグループの動機の解釈を修正しました。分析の結果、実際には破壊工作を行うイラン国家主導グループであることが判明したため、CTU はグループ名を COBALT AZTEC に変更しました。他にも、COBALT SAPLING、COBALT MYSTIQUE、COBALT SHADOW といったイランの脅威グループは、偽のハクティビストを装い、イスラエルやアルバニアの特定組織を標的に妨害目的のランサムウェア攻撃やデータ窃取攻撃を仕掛けています。

同様に、ロシアも 2022年以前にウクライナの金融業界に対して複数回ランサムウェア攻撃を仕掛けました。その中で最も有名なのが NotPetya です。被害を受けた組織の中には、身代金を支払ってシステムの復旧を試みたところもありましたが、攻撃者は金銭目的ではなく、また自らのブランド構築も意図していなかったため、復号ツールを提供しませんでした。

これらの攻撃の主な動機は金銭ではありませんが、一部の国家主導グループが被害者と身代金交渉を行って支払いを強要する可能性は十分あり得ます。しかし、証拠によれば、それは標的選定の決定要因というより、あくまで利益の出る副業に過ぎないと考えられます。特にイランのグループは、攻撃の認知度を高め、被害組織にさらなる政治的ダメージを与え、イスラエル政府の信用を失墜させる目的で、交渉の詳細をあえてリークしています。こうした活動は、攻撃者の特定を一層複雑なものにしています。

結論

ほとんどのランサムウェア攻撃は、サイバー犯罪者が金儲けのために行う無差別なものです。攻撃者は、特定の標的へのアクセスを試みるよりも、すでに手に入れているアクセス権を悪用します。被害者の選別が行われるとしても、それはアクセス権を入手した後のことです。したがって、組織は「標的にされる」というより、「被害者にされる」のだといえます。スキルの高いランサムウェアグループやアフィリエイトもいれば、そうでない者もいますが、どのグループによる攻撃であっても、被害組織に甚大な影響を及ぼす可能性があることに変わりはありません。したがって、ネットワークの防御担当者は、自社環境におけるテクノロジースタックを踏まえて、あらゆるランサムウェアグループやアフィリエイトが使用するツール、戦術・手法・手順 (TTP) について考慮すべきです。

CTU の研究チームがランサムウェア対策に関する推奨事項を繰り返し強調するのは、これまで観測・分析したほぼすべての侵入事例において、被害組織がそれらのガイダンスに従っていなかったためです。確かに、ネットワーク環境は往々にして複雑で管理が難しく、推奨事項の実施は簡単ではありません。しかし、いかなる組織においても最優先事項として位置付けるべきです。

- インターネットに公開されているサービスにパッチを適用すれば、毎日実施される定例の脆弱性スキャンによって検知されるのを防げます。

- すべてのユーザーアカウントに、できればフィッシング対策機能を備えた MFA を確実に適用することで、盗まれた認証情報や収集された認証情報が再利用されてアクセスされるリスクを排除できます。

- EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) ソリューションを導入すれば、検知と修復の機会が大幅に増加します。

- そして、イミュータブルバックアップを導入することで、ランサムウェア被害から迅速に復旧でき、通常業務への早期復帰が実現します。

.svg?width=185&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.svg?width=13&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)